A ceramic panel presenting Jingdezhen's Taoyangli area, where porcelain has been made for 1,700 years.[Photo provided to China Daily]

In the old days, children in Jingdezhen, East China's Jiangxi province, had their own novel way to keep themselves warm during the chilly winters. They took a warm brick from a firing kiln and put it in their schoolbags.

They don't need warm bricks in cold seasons of the year now, but kiln bricks are still used for building houses in Jingdezhen, known as the "home of porcelain" in China and even across the world. Brick kilns have to be demolished every two or three years to ensure they maintain a certain heat output, according to local ceramists.

The Jingdezhen Imperial Kiln Museum, designed by the Beijing-based Studio Zhu-Pei, incorporates both newly fired and recycled bricks amassed from the dismantled furnaces. Located in the center of the city's historical area, the museum is adjacent to the imperial kiln ruins surrounded by many ancient kiln complexes.

Recycled kiln bricks still provoke warm memories among the local residents.

"The ancient kilns in Jingdezhen have never stopped firing for more than 1,000 years. And the whole craftsmanship for hand-making porcelain has been maintained, which makes the city what it is today," says Wang Tongmao, deputy secretary-general of the city government.

Along with the old lanes and houses, the ancient kilns are the links the city has with its past.

One of the small alleys in Jingdezhen, where artisans have made porcelain for 1,700 years.[Photo by Cai Hong/China Daily]

The early settlement of Jingdezhen was developed around kilns, which were built along the Changjiang River and its branches. Local people used the kilns as social and public gathering spaces. As a result, a unique culture developed, which was, and still is, closely connected to porcelain production.

In 2015, Jingdezhen put its imperial kilns used to fire porcelain for the courts in the dynasties of Ming (1368-1644) and Qing (1644-1911) forward in a bid for United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization's World Heritage Site status.

Between 2017 and 2023, the city added more kilns used from late Tang Dynasty (618-907) to the Qing Dynasty to its bid package in the hope of presenting more details of its porcelain-making history.

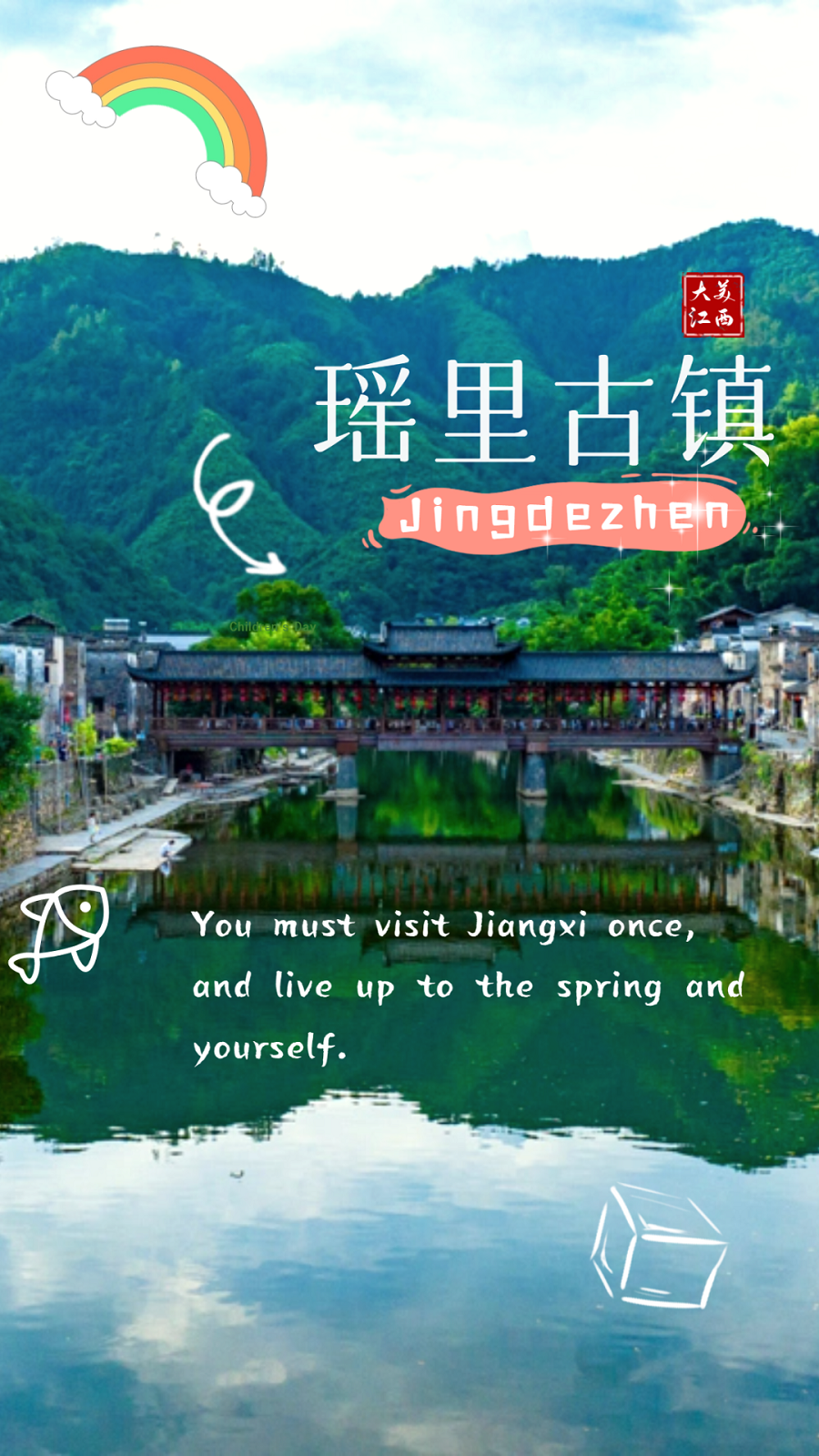

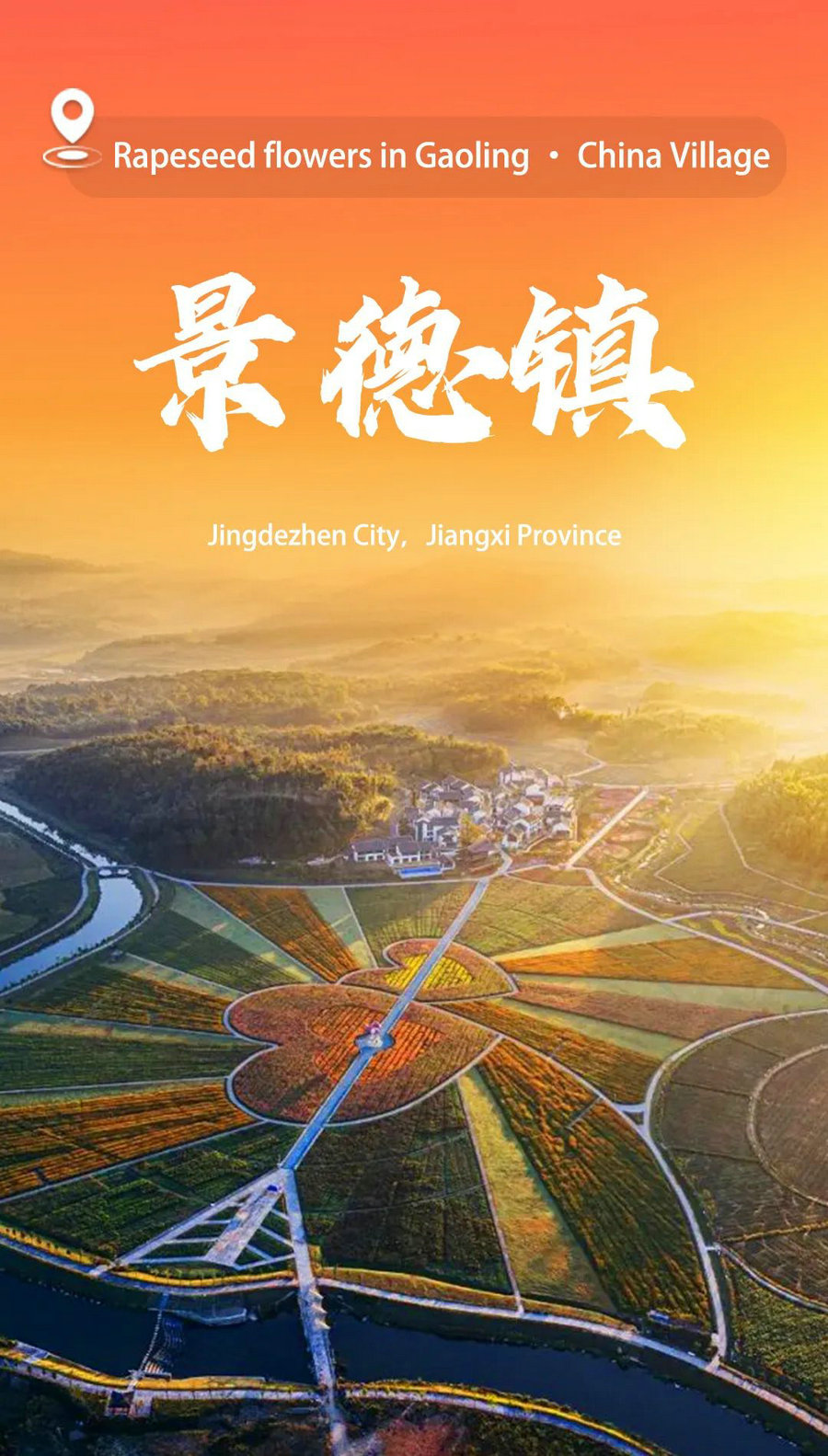

In July 2023, the city rolled out a brand-new strategy to apply to become a UNESCO World Heritage Site. It includes the old district of the city, and some areas such as Gaoling, Yaoli and Jiaotan that used to provide kaolin clay and wood, as well as the river system.

"The time-honored kilns are not the whole picture of the city," says Wang, who also doubles as the director of Jingdezhen's office for cultural heritage application and protection.

"The new strategy highlights the history of Jingdezhen's porcelain industry and city building."

Jingdezhen Imperial Kiln Museum's design and contents pay homage to the city's ceramic tradition.[Photo provided to China Daily]

The city is conducting an exhaustive investigation of the underground relics and its layout, including kilns, buildings, streets, alleys, river systems and wharves.

The areas related to the porcelain making will make it to the city's conservation plan, while new archaeological findings in the future will also be put on the conservation list, according to the official.

"We want the conservation plan to be the most authentic and complete picture of Jingdezhen's ceramic-making industry and city building," he says.

Old district

Jingdezhen was previously known as Changnan, which literally means "south of the Changjiang river" in Chinese. In 1004, Emperor Zhenzong of the Song Dynasty (960-1279) was so enchanted by the translucent beauty of white porcelain from the town that he renamed it Jingde after the name of his reign.

It is on the bank of the Changjiang River, which flows from the mountains that separate northeastern Jiangxi from neighboring Anhui province. The city stands at the point where the river exits rocky gorges and loses its swiftness, broadening into a shallow, curving basin 5 kilometers long. Dozens of streams flowing into the basin powered waterwheels and iron trip hammers that crushed rocks used for making pottery.

The city's layout was generated by nature and the porcelain industry. What makes Jingdezhen's old district special is the network of the long, narrow alleys extending in all directions along the Changjiang River. They are in between the kiln complexes.

The old district has been kept almost intact, with more than 100 alleys and some 100 buildings dating to the Ming and Qing dynasties, according to Wang.

Most of the alleys still have their original names. Some are named according to regions, such as Fuzhou alley and Hukou alley. Others are named after a particular business, such as firecracker, pawnshop and straw sandals, while some are named after surnames like Zhan, Bi, Peng and Fang.

A kiln dating to the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644) has been reignited to fire porcelain in Jingdezhen.[Photo provided to China Daily]

The alleys were communities where craftspeople and their families worked and lived and there were hostels for dealers from other parts of the country.

Local ceramists used the Changjiang River to bring down clay, firewood and other raw materials from mountains nearby, as well as to transport their products to the outside world.

Jingdezhen has witnessed ceramic making for more than 2,000 years, including more than 1,000 years for official kilns and more than 600 years for imperial kilns. It has developed the porcelain-making techniques that put it in a league of its own, and by the mid-15th century, all of China's imperial porcelain came from Jingdezhen.

"The ceramic sector alone has served as Jingdezhen's most crucial economic pillar for nearly 2,000 years," Wang says.

"It was the world's largest industrial city in the early 18th century."

What Jingdezhen contributed to the history of porcelain industry, in Wang's words, was organization.

"Jingdezhen traditional ceramics have a very fine division of labor in production. It ensures the exquisite Jingdezhen ceramics," Wang says.

In his famous book The Wealth of Nations, Adam Smith explains that division of labor in production increases as the market for merchandise expands.

Coordinated effort, specialized skills and standardized replication of wares were the only way for Jingdezhen to fill short-term orders for huge amounts of porcelain from seagoing merchants in other parts of China.

From the Ming Dynasty onward, official kilns were designated as suppliers for the emperor, with private producers also drafted into service when Beijing's demands outran the capacity of the imperial furnaces.

Mass production was evident in the operation of kilns as manufacturers specialized in certain items, such as storage jars, fishbowls, wine cups and lanterns. Some kilns produced replicas of porcelains from the Song Dynasty; others copied bronze vessels from the Shang Dynasty (c. 16 century-11th century BC) or jade cups from the Han Dynasty (206 BC-AD 220).

Making porcelain in Jingdezhen was — and remains — a collective endeavor requiring as many as 169 kinds of workers, such as potters, painters, kiln workers, china stone miners and processors, men to make knives for trimming, transporters of unfired green-ware, glaze producers, mold-makers, and men to make saggar, build kilns and pack finished wares, Wang says.

A water-powered trip hammer in Jingdezhen's Yaoli town is still in use.[Photo provided to China Daily]

Successful renovation

Dong Lin, who teaches arts at the Beijing Union University, works on ceramic panels and sculptures at her studio in Jingdezhen on every summer and winter break.

"I love Jingdezhen so much as it has everything I want to make ceramic artwork," says Dong, who is a PhD graduate of ceramic art from the Central Academy of Fine Arts.

After the founding of the People's Republic of China in 1949, all the family-run workshops in Jingdezhen were regrouped into 10 State-owned pottery plants, and mechanized porcelain production started there.

These factories ran brilliantly for decades, and their products were exported to countries around the world, earning heaps of foreign exchange for China.

In the 1990s, these plants lost their edge as their counterparts in Fujian and Guangdong provinces had better equipment and technology. The factories shut down, and their workers were laid off. Family ceramic businesses restarted in Jingdezhen.

To keep its unique porcelain culture, Jingdezhen has launched a large-scale conservation and renovation campaign to protect its ancient imperial kiln sites, as well as the old residential buildings and workshops.

An aerial view of the ruins of a kaolin clay mine in Jingdezhen's Yaoli town, Jiangxi province.[Photo provided to China Daily]

Pengjia alley, for example, is one of the projects on the renovation list. The community has a large area of porcelain-making ruins. The Tsinghua Tongheng Urban Planning and Design Institute restored the entire original structure with expertise and considerable love and attention to detail, and carefully supplemented with new buildings. Its approach makes the history of porcelain making not only visible to residents living and working there, but also enables it to be experienced by tourists.

"Historical ruins have been transformed into a lively place for living, shopping and culture, while ensuring that the past can still be felt everywhere," says Zhang Jie, professor of architecture at Tsinghua University in Beijing.

Zhang's team and other architecture firms have also helped Jingdezhen redevelop an extensive area of old, large factory buildings as a new mixed-use quarter called Taoxichuan Ceramic Art Avenue. They preserve, restore and convert the old buildings while complementing them with new buildings.

Zhang was granted the gold and silver awards at the 2023 International Design Awards for his innovative work in Taoxichuan and Pengjia alley projects. They are lauded as a remarkable fusion of traditional culture with urban regeneration, which underscores the significance of preserving industrial heritage and historical relics within the global design narrative. These areas have been revitalized into dynamic hubs for residential, commercial and cultural heritage showcases.

"Our approaches are aimed at preserving Jingdezhen's historical landscape, including the ancient residential buildings along the Changjiang River, workshops, lanes, public facilities and ancient wharves," Zhang says.

The historical remnants of the imperial ceramic workshops on the site of the Pengjia alley, uncovered by archaeological excavations, have been injected with new life, while maintaining great respect for the culturally valuable remains. The combination of historical architecture and modern design has succeeded at a high formal and functional level. The result is an extraordinary place that plays with the contrast between old and new in a charming manner. With its different cultural offers, it invites visitors to go on a fascinating journey of discovery.

"When the rest of Jingdezhen's old area is restored to its original look, the city will be in a class by itself," Wang says.

China's National Cultural Heritage Administration has sent four teams from the National Center for Archaeology, the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, Peking University and the Palace Museum to help Jingdezhen find the underground relics. Archaeologists from Jiangxi province also joined the digging in the city, Wang says.

Jingdezhen's conservation of tradition, like the wood-fired kilns, has been a success. From 2009, 10 classic types of old kilns have been re-burned.

"We need to pass down our cultural heritage because that is the soul of the city," Wang says.

来源:中国日报

Source: China Daily

校对:唐婷玉

Proofread by: Tang Tingyu

编辑:黄乔珺

Edited by: Huang Qiaojun

复审:占妍

Reviewed by: Zhan Yan

终审:陈俊绮

Final Reviewed by: Chen Junqi